Most visitors standing on the concrete walkways at Vøringsfossen never realise what sits hidden just below them. Only a few metres away lies Måbødalen, one of Norway’s most remarkable early road-building achievements, now fenced off, blocked by landslides, and left to decay in silence. It’s an uncomfortable contrast: a hand-built masterpiece abandoned, while vast sums are poured into car parks and viewing platforms designed for fast, high-volume tourism. Specticle over substance. Consumption over meaning..

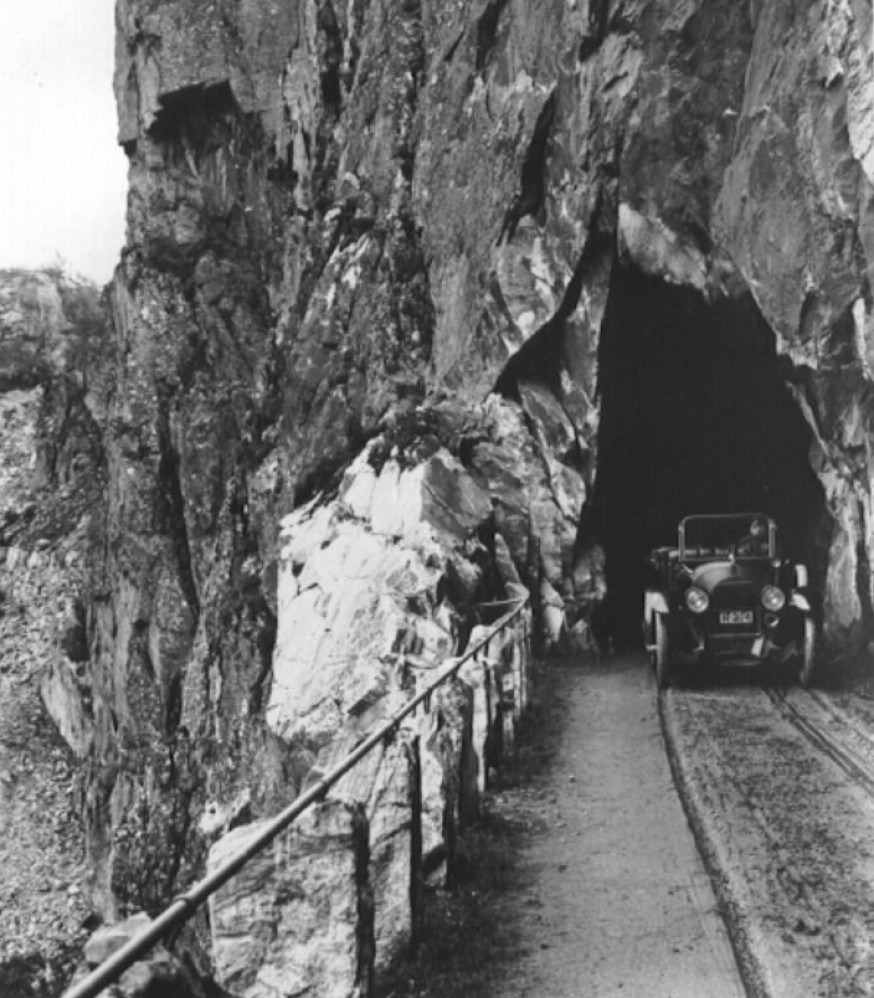

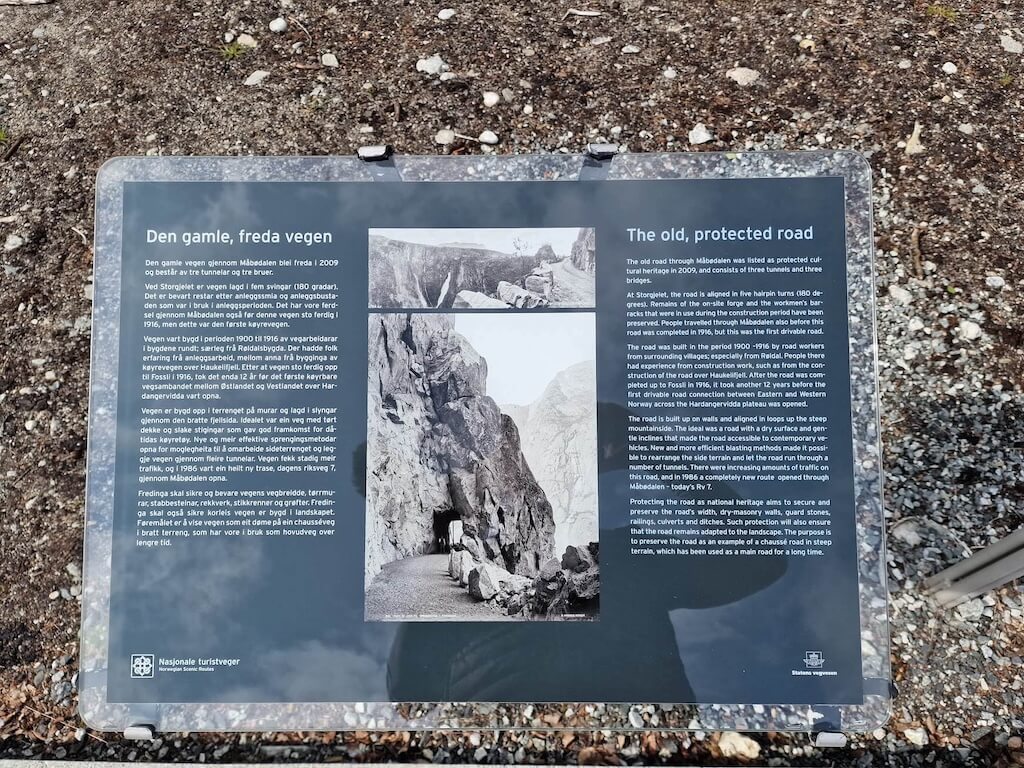

The old road through Måbødalen was built between 1900 and 1916, carved directly into the gorge by workers using picks, chisels, stone, and dynamite. They created terraces, dry-stacked stone walls, tight hairpins and three hand-cut tunnels that brought travellers up from Eidfjord into the mountains. When the final links over Hardangervidda were completed in 1928, the road became the first proper east–west connection between western Norway and the inland plateau. For decades people rode horses, drove early cars, walked, pushed bikes, and moved goods along this steep, exposed, unforgettable route. It was infrastructure built on human terms, not machine terms.

Photos above from – Norsk Folkemuseum

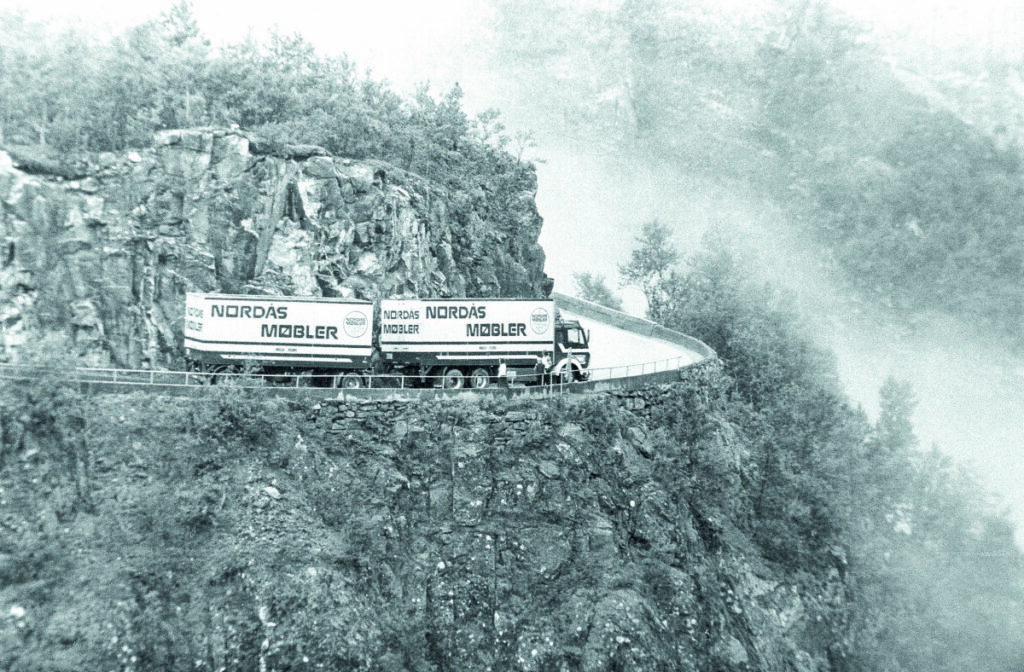

By the early 1980s, traffic had changed. Heavy lorries struggled on the steep descent, winters were unforgiving, and the geometry of the old hairpins simply didn’t suit modern transport. A new alignment of Rv7 was built with four modern tunnels, including the 1.9 km Måbø Tunnel. Construction finished in the mid-1980s, and the new road officially opened in 1986. For a short period both alignments functioned side by side, easing traffic and giving drivers a choice between the new tunnels and the old open road.

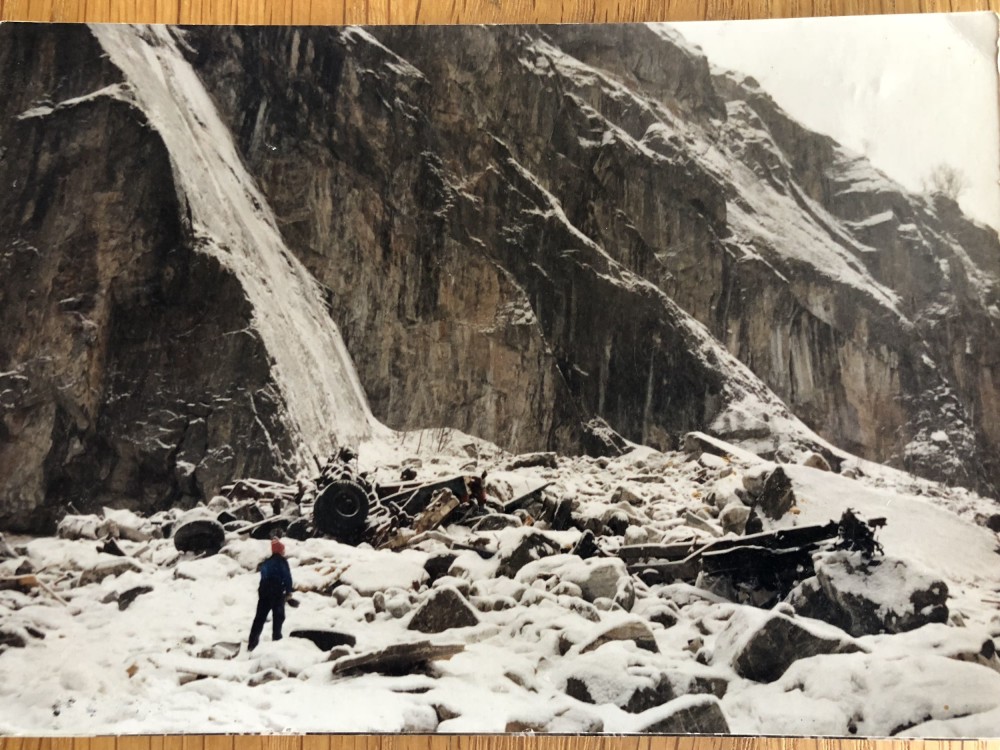

But the limits of the old alignment showed themselves quickly. In the winter of 1987, a year after the tunnels opened, two heavy trucks lost control on the upper section of the original road. Both drivers jumped from their cabs at the last second and survived, while their vehicles plunged roughly a hundred metres into the gorge. These incidents didn’t cause the closure of the road; it was already redundant for most traffic, but they underlined why the tunnels had been built. The old route simply belonged to another era.

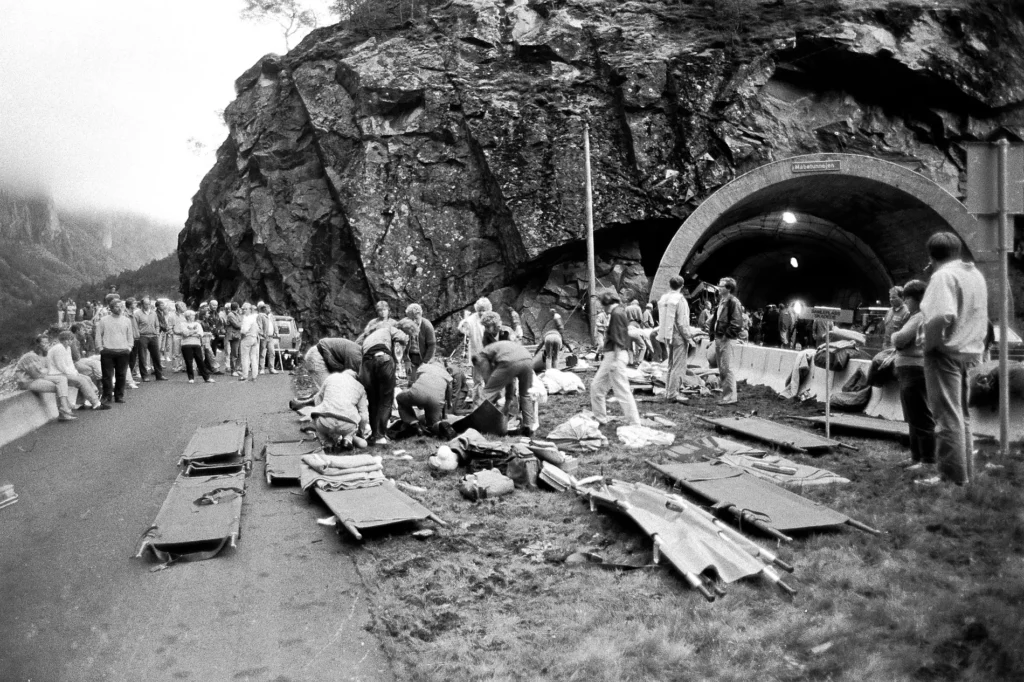

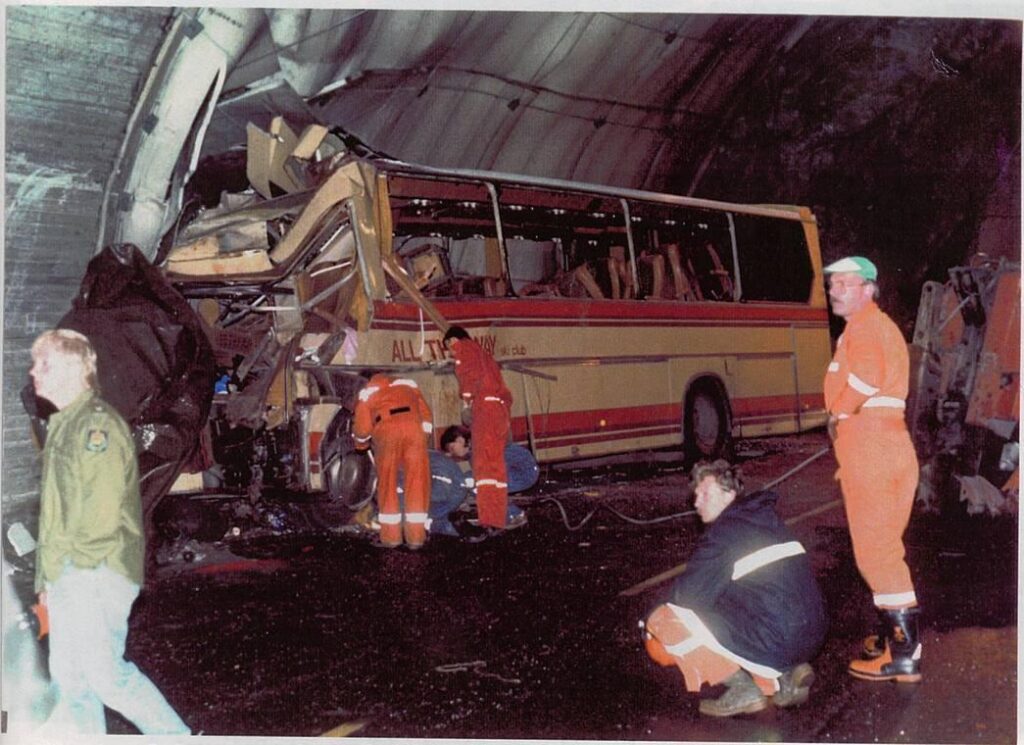

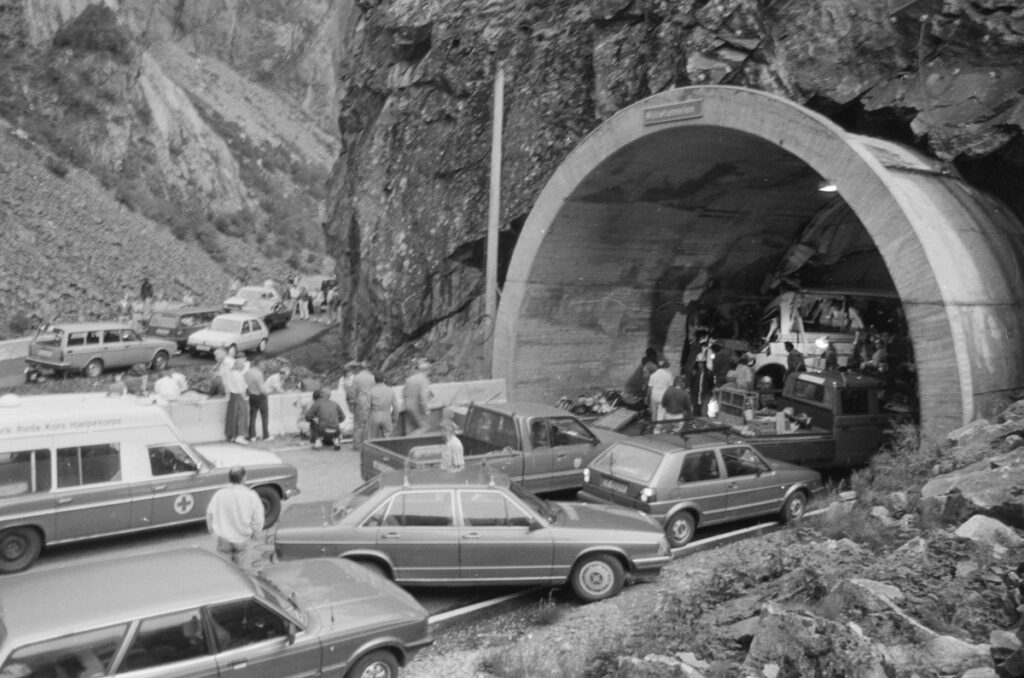

Sadly, however, even the new alignment proved demanding. In 1988, a Swedish school bus crashed inside the new tunnel system after suffering brake failure on the long descent into Eidfjord. Sixteen people died, including twelve children. Making it one of the worst traffic fatalities in Norwegian history, and showed just how unforgiving this valley was for heavy vehicles, especially with the braking technology of the 1980s.

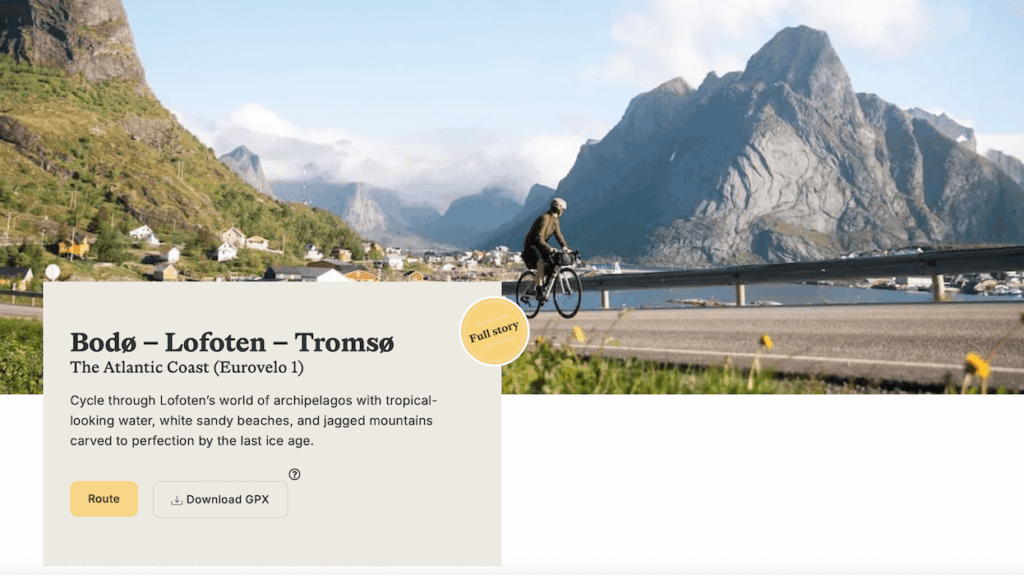

In the years that followed, the old road closed completely to vehicles, while the new tunnels gradually became safer as technology and braking systems improved. With lorries and buses gone, the old alignment quietly found a second life. Cyclists began using it in growing numbers, drawn to its steady gradient, dramatic views, tight switchbacks and the sense of climbing into Hardangervidda along a historic, human-scaled route. It became a highlight for touring cyclists crossing Norway, a defining ascent in the Voss–Geilo race, and was praised internationally as one of the country’s finest climbs, quiet, demanding, scenic and utterly unique. Even today it would offer a safer and far more meaningful option for events like Norseman, which currently must cycle some of the main tunnels never designed with cyclists in mind.

Yet while cyclists and hikers quietly embraced it, the state did the opposite. No repairs were made. Landslides were slow to be cleared. No real stabilisation work was carried out. Vegetation grew through the stone walls, and small collapses were simply left where they fell. Eventually, 600–700 metres of the road became impassable, and fences were erected to block off the entrances entirely. On paper, the route was given formal cultural protection. In practice, it was abandoned.

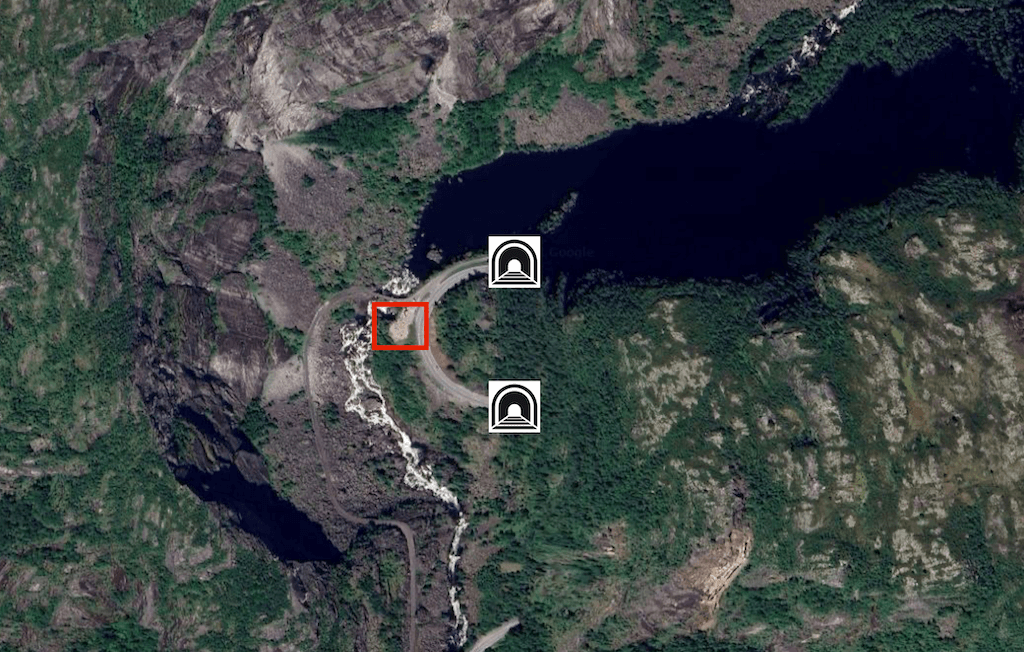

And as this one route decays, just a little further up the valley, a new expensive and pointless rest-area has been erected: the Måbø Bridge “rasteplass”. Located along Rv7 at the outlet of Lake Måbøvatnet and between two narrow tunnels, this rest stop was upgraded this year with benches, planting, accessible facilities, all with the stated goal of “an open and friendly place that invites travellers to take a nice break in beautiful surroundings.” But genuinely beautiful surroundings here include two dangerous tunnels and hairpin bends not designed for stopping traffic. It’s an odd place for a rest-area: a car pulls off from a narrow, winding mountain road, stops between two tunnels, then re-enters the flow. The location raises obvious questions about traffic safety and whether adding a stopping point on a sharp mountain stretch makes sense. Whenever you build for cars first without regard for human speed or alternative access, you degrade the experience you claim to be enhancing.

The irony is hard to ignore. While the old road sits behind steel fences, tens of millions of kroner have been poured into serving motorised tourism. At Vøringsfossen, the region’s flagship waterfall, the priority has been to handle ever-growing volumes of cars, buses and motorhomes. Massive car parks, broad walkways, steel viewing structures and expanses of hard landscaping now dominate this fragile area once adored by artists and poets seeking inspiration from the unique nature. Today, everything is built for quick-stop, high-throughput tourism. The message is clear: get people in, give them the viewpoint, and move them on.

Meanwhile, the one piece of infrastructure that could genuinely diversify the visitor experience, reduce pressure on the viewpoint, and offer a slow, human-scale alternative has been allowed to rot. Måbødalen is not just neglected. It has been erased from the tourist narrative entirely. One small meaningless sign briefly tells its story at the edge of the huge new Vøringsfossen car park. No boards explain its engineering. No access is provided to people who travel on foot or by bike. It is treated as if it never existed, even though it lies directly beneath the state’s largest tourism investment in the region.

The possibilities are obvious and frustratingly doable. The road could be stabilised and restored as a car-free ascent into Hardangervidda. The excuse right now is that the area is too unstable and the cost to make it safe is too high. Yes, it would be a huge cost if no one used the restored road. But think long term. A bike rental point in Eidfjord could turn it into a full-day experience for visitors. Storyboards could bring the century-old engineering back to life. Cycling events could return. Hikers could move through the landscape on the original alignment instead of standing shoulder to shoulder on a concrete platform. In short, it could become one of Norway’s finest examples of slow tourism, heritage, scenery, exercise, and culture all woven into a single route.

None of this is unrealistic. The road already exists. The demand already exists if you market it correctly. The modern cycling boom is global, and Hardangervidda is a world-class setting. The only thing missing is leadership, innovation, and a willingness to break out of car-first thinking and recognise that tourism built around speed and convenience eventually destroys the very qualities people come to see.

What has happened in Måbødalen is not just an oversight; it is a symbol of a government drifting without a clear tourism vision. The safe option, the comfortable option, is to keep building bigger car parks, bigger rest stops, bigger viewing platforms, and bigger access roads. The difficult option, the meaningful option, is to restore the pieces of history that give Norway its depth. One path is easy concrete; the other is careful stewardship.

Måbødalen deserved better. It could have been, and still could be, a centrepiece of sustainable travel in Hardanger. Instead, it stands as a monument to lost opportunity: a masterpiece hidden behind a fence, decaying quietly while modern Norway pours its energy into traffic management and visitor throughput. The road is not beyond saving, but the longer it sits untouched, the clearer the message becomes: if a piece of heritage cannot be reached by car, it no longer matters.

Cycle Norway won’t accept that. Norway is sleepwalking into a tourism crisis by doubling down on the same habits, a style of cheap, Instagram-ready tourism that treats the landscape like a stamp collection. This fast-food version of travel has nothing to do with Norway’s real character. It rejects the slower, harder, more grounded way of experiencing the land, the way that shaped the culture in the first place. The tide will turn; it has to. Our job is to show what’s at stake: a country trading depth for convenience and identity for volume. This old road is a warning of what Norway stands to lose if it keeps choosing the path of least resistance.

“In 2022, I cycled this road as part of my Fjord Norway journey. Officially, the road is closed to cyclists and is not maintained for public use. Anyone choosing to ride it does so entirely at their own risk, and Cycle Norway cannot recommend or endorse cycling here.

That said, the reality is that many riders continue to use the old road, and its historic value and potential as a cycling route are well known within the community. My role is to document the route’s condition and its importance, not to encourage breaking regulations. If you decide to explore it, make sure you fully understand the risks, the legal status, and the fact that access may change.”