Go Further North

A Long Ride Through the Arctic of Europe: From the forests of Finland to the fjords of Norway and the wilderness of Swedish Lapland The

A Long Ride Through the Arctic of Europe: From the forests of Finland to the fjords of Norway and the wilderness of Swedish Lapland

The far north of Scandinavia is often seen as remote and desolate. Endless forests, open tundra, and skies that never seem to end. But for the adventurous cyclist, it offers raw beauty, forgotten histories, and a solitude that’s hard to find elsewhere in Europe.

My journey covered over 2,300 kilometers through the Arctic and Lapland, beginning in eastern Finland and ending in Sweden, with a demanding stretch through Norway in between. Finland gave me quiet forests, rough gravel, and reindeer-lined roads. Norway tested my stamina with high plateaus, cold wind, and a barrenness that pushed my setup to its limit. By the time I reached Sweden, the landscape softened slightly, but the sense of isolation remained.

Each country brought a shift, not just in terrain, but in atmosphere. It was a test of endurance, but also a rare chance to disconnect and move through one of Europe’s last true wilderness regions. Days passed without seeing anyone. Just wind, gravel, and the rhythm of the ride.

Text and Photography by Michel Alexander: An adventure bikepacker from Denmark with a passion for pushing boundaries. Never one to shy away from a challenge, he seeks out epic journeys that take him far beyond the ordinary, on two wheels and off the beaten track.

EuroVelo 13: The Iron Curtain Trail

My journey began with a quiet ride on Finnish backroads, leading me to Suomussalmi, where I joined the EuroVelo 13 “Iron Curtain Trail.” This route follows the historical Cold War frontier and runs from southern Finland all the way to the Norwegian border. In this region, it largely follows Road 843, a quiet, rural stretch that winds through deep forest and tranquil lake country. For the first few days, the riding was smooth, the traffic nearly nonexistent, and the landscape, while beautiful, was repetitive enough to dull the senses.

The trail offered little variation for long stretches, and eventually it joined the busier E63. While not ideal for cycling, sometimes there’s no way around it when traveling through sparsely populated terrain. That said, Finnish drivers were mostly considerate.

After passing Hossa National Park, an incredible place for hiking or mountain biking,I veered off the main route and into the gravel wilds along the Russian border. These roads varied dramatically: some were freshly graded, others deeply rutted or loose with stone. I rode in zigzags, climbing and descending through endless boreal forest. There were few villages, no cafés, and barely a soul in sight. I would go for hours without seeing another human being.

Traces of the Past Along the Border

The terrain was wild, but human history lingered here. The Finnish-Russian borderlands are full of war memorials and remnants of old defense systems. In 1940, tens of thousands of Finns constructed a massive 1,200 km defense line to guard against possible Soviet invasion. Many of the giant rocks and bunkers they installed still sit hidden among the trees, a silent witness to past struggles.

Some of these places have faded from collective memory. They’re overgrown, rusting, broken, but still powerful. Riding through these sites made the landscape feel less empty, like something was watching, listening.

Eventually, I rejoined the EuroVelo trail on Road 950 near Oulanka National Park. Forests gave way to more dramatic hills, river valleys, and the occasional swamp. The road undulated constantly. No big climbs, but the continuous up-and-down wore on the legs. Every crest gave a view of more trees and more sky.

E75 and the Push North

North of Sodankylä, options became limited. For 90 km, I was forced onto the E75, a main arterial road with no practical detours. There’s not much to say about it, just head down, legs spinning, eyes on the shoulder. It was a necessary evil to reach the next stage of the journey.

After Ivalo, the journey took on a new character. While most travelers heading to Kirkenes veer west around Lake Inari, I took the lesser-known route east on Road 969 toward Nellim. This road twisted and undulated through deep forest and over steep hills before crossing the Paatsjoki River, the natural border with Russia.

From the bridge, you can see the Russian shore just a few hundred meters away. There are no signs of habitation, just silent trees. It was one of the eeriest, most thought-provoking moments of the journey.

The gravel road continued for 20 km, winding and empty. Eventually, I reached the Finnish border zone, a restricted area no civilian may enter. But from here, a rough trail, an old border guard path, leads to the tripoint where Finland, Norway, and Russia converge.

The Border Guard Trail and Treriksrøysa

The 15 km trail was brutal. It alternated between rideable sections and unrideable terrain filled with rocks, rotting duckboards, fallen trees, and deep swamp. Sometimes I had to drag my bike through mud, other times I had to shoulder it up steep inclines. It was remote, exhausting, and slow.

Midway, I took a long break at a decaying border guard station in the middle of nowhere. Its presence felt ghostly, a reminder of how isolated this path once was, and still is.

The trail refused to be predictable. At one moment, it would seem like a clear path over firm ground; minutes later I’d be ankle-deep in swamp water trying not to lose a shoe. Every kilometer required full concentration and physical effort. There were moments I questioned whether I should turn back.

But after nearly seven hours, I reached Treriksrøysa. It’s a modest pile of stones, but symbolically important. It marks the exact meeting point of Finland, Norway, and Russia. Two young Norwegian soldiers greeted me, surprised to see someone arrive by bicycle from Finland. They took my photo and kindly chatted for a while.

I wasn’t allowed to touch or walk around the marker; it’s a protected boundary zone, but standing there, at this distant point in Europe, I felt an overwhelming sense of accomplishment. Only 11 visitors made it that day. For me, it felt like reaching a spiritual summit.

Øvre Pasvik National Park and No-Man’s Land

The descent on the Norwegian side wasn’t much easier. The first few kilometers were rough, with uneven rocks and more duckboards. Eventually, I reached a gravel road and followed it north, camping near the Pasvik Nature Reserve.

I had no phone reception for over 24 hours, a rare experience in Scandinavia. It made me realize how thoroughly connected we’ve become, even in wilderness. Here, I was truly alone.

Fv 8550 is the only road through the Pasvik Valley. It’s bumpy, patched up in places, and usually empty. Occasionally, I’d catch glimpses of Russia across the river. My first stop was Infopunkt Gjøken, a small open-air exhibition of log cabins and border life, complete with a sheltered rest stop and power outlets.

Later I detoured to the Skrøytnes birdwatching tower. Cotton grass danced in the wind and cloudberry flowers bloomed all around. The air was clean, the silence total.

In Svanvik, I restocked at the Coop. Soldiers were everywhere, but it didn’t feel tense, just quietly watched. The military presence was friendly, understated. We exchanged nods, and I moved on.

That evening, the road led to big lakes and deep valleys. The landscape opened up again, and a golden evening sun cast a glow over the water. I stopped to photograph reindeer grazing by the roadside. They didn’t flinch as I passed by.

Kirkenes and the Coast

North of Svanvik, the road improved. Lakes grew larger. Eventually, I rode along the Langfjord under the golden sun. The road was empty, the landscape wide. When I reached Kirkenes, I skipped the town center and continued into the hills.

At Korsfjord, reindeer grazed alongside the road. Here, I met Fetze, a fellow cyclist heading toward Pasvik. His setup was far better equipped for off-road travel. We rode together for a while under the midnight sun before parting ways.

At Neiden, I pitched my tent beside Skoltefossen. The waterfall glistened in the soft light, making it a memorable place.

The next morning, I bathed in the river, a cold but refreshing wake-up. I then visited the Ä’vv Skolt Sami Museum, which offers a deep insight into the culture and craftsmanship of the Skolt Sami people. They had replicas of old riverboats, made for specific currents and fishing techniques. One such boat, available for public use, floats in Skoltebyen near the falls.

Into Sami Land and Spiritual Places

The E6 followed broad swamp flats toward Bugøyfjord. From there, I hiked up to Saviostolen, a seat-shaped rock where Sami artist John Savio once found inspiration. Reindeer grazed nearby. The view of the fjord and marshes below felt timeless. It was a simple walk but a powerful moment of perspective, away from the bike and the road.

Back on the saddle, I pushed toward Varangerfjord. The road twisted beside crashing waves and towering cliffs. The wind made progress slow, but the changing light and dramatic views made up for it. At the Varanger Sami Museum, I stopped for dinner in a public shelter. I’d visited the museum two years earlier, its exhibits on Sami life and fjord settlements are some of the best in northern Norway.

Although I was tempted to cycle further east toward Vardø, a wild and wind-beaten island I had visited before, I turned west instead. A steep climb of 160 meters took me inland again. Soon, the Varanger coast gave way to the broad, quiet Tana River valley. Here, the landscape changed again: wide sandbanks, pine forests, and a slower, more reflective pace.

I pitched my tent late above the riverbanks. It was a still and silent night, the kind where even the seagulls seemed to rest.

Rain, Fjords, and Pebble Beaches

I delayed my start the next day, waiting out a stubborn rainstorm. My body needed the rest. Eventually, I pushed on to Rustefjelbma, where I found coffee and warm food at the gas station. From there, the road turned west, rolling endlessly across lakes, tundra, and low ridges.

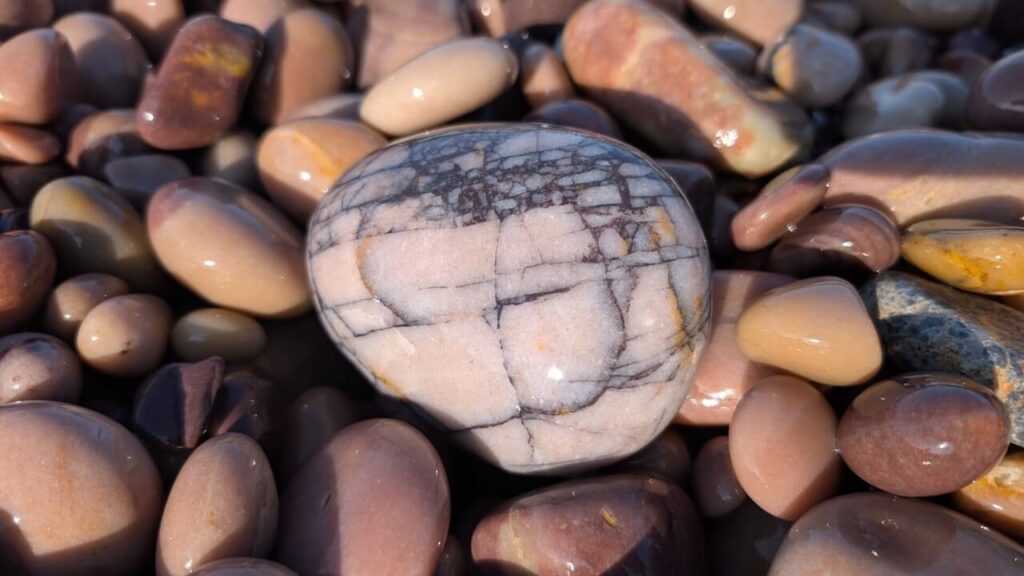

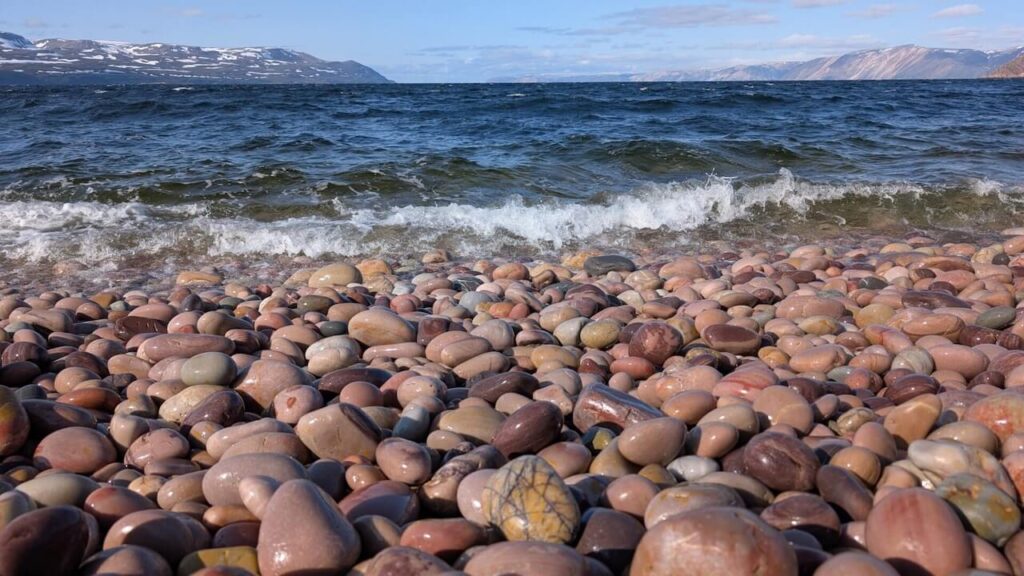

I met a Dutch cyclist coming the other way. He warned me of rain and cold, but as we parted, the sun broke through the clouds. My next stop was Rullesteinfjæra, a remote beach where waves polish stones of all shapes and colors. The hike was just over 2 km each way, across rough paths and boggy sections, but the place itself felt magical.

The stones clicked softly in the surf, catching sunlight in a dozen shifting hues. I sat there for an hour doing nothing but watching the tide, completely absorbed by the rhythm of the water and stone. On the walk back, I noticed that every step over the pebbles created its own quiet music.

Into the Heart of Nordkyn

It was late when I began the long climb to the Ifjordfjellet plateau. The light raked across the hills, casting long shadows and illuminating herds of reindeer. The road wound higher through a cold, lonely landscape of snow patches and rocky scrub. At Ifjord, I turned onto road 888, which snakes 33 km along the edge of Laksefjord.

I rode into the night, the midnight sun still hanging above the horizon. Eventually I stopped and camped in the Laggu Nature Reserve, sheltered between two hills.

In the morning, a snow shower hit as I woke. The temperature had plummeted. I put on every layer I had and packed up in a hurry, fingers numb, the tent soaked. The wind came from the north and battered me for most of the day.

The road climbed again, this time past Reinoksevannet, a lake still partially frozen in late summer. The land was bare, dotted with old snowdrifts and glacier-fed streams. Sun and hail alternated every few minutes. A long descent brought me down to sea level and into the narrow land bridge connecting Eidsfjord and Hopsfjord.

But there was no rest. The road climbed again, steep and unrelenting, towards the final plateau before Mehamn. Up here, the weather is king, and the scenery feels closer to the edge of the world than almost anywhere in Europe.

Eventually, the road plunged down to the coast, and I rolled into Mehamn late in the day. It felt like the end of something. I’d come so far north. But nature wasn’t done yet.

The Final Push to Slettnes Lighthouse

I’d planned to take the Havila coastal ferry that night, but at midnight I received a call from the crew: the boat wouldn’t stop in Mehamn due to high seas. My only option was to cycle another 30 km over the mountains to Kjøllefjord, where the ship could dock.

I packed, layered up, and hit the road again at 1 a.m., climbing into the wind and cold. The journey felt endless. At times, I wasn’t sure whether I was fighting the terrain or the weather, or both. By the time I reached Kjøllefjord at 3:30 a.m., I was soaked and spent. Thankfully, the ferry crew gave me a cabin to recover.

After just a few hours of sleep, I disembarked at Havøysund and headed inland along Road 889. This stretch was dramatic: the sea on one side, jagged cliffs on the other, and endless wind. I passed a group of American cyclists dragging trailers, each one looking like they were questioning their life choices on the long climb ahead.

Sculpted rock formations, like the so-called “Sphinx” or “Lion of Måsøy” rose from the hills like ancient guardians. I left the coast and crossed the Porsanger Peninsula toward Skaidi, stopping for coffee and warmth at Russenes Kro.

Crossing the Arctic Plateau to Alta

Sennalandet is the kind of place that strips you down. There are no trees, no cover, only wind and sky. Reindeer drift like ghosts across the snow patches. The road undulates endlessly. It was here I realized how much my legs were asking for a break.

Descending into Alta felt like re-entering another world. Trees returned, the river wound slowly through the valley, and people fished the banks in the late evening light.

The Old Arctic Post Road and Into Sweden

From Gargia Lodge, I took the Old Arctic Post Road, a historic mail route that now serves as one of the finest gravel cycling experiences in the north. It began with a steep 300-meter climb that no campervan should ever attempt, but they do.

After a few kilometers, I stashed the bike and hiked to Alta Canyon, one of the biggest ravines in northern Europe. The walk was long but worthwhile, with views into a thunderous chasm where the Alta River carved through rock over millennia.

Back on the gravel road, things got rough. Potholes, washouts, and boggy tracks forced me off the bike regularly. I crossed streams, rode through flooded sections, and dragged the bike over rock-strewn hills. The views, though, made it worthwhile: wide alpine plateaus, snow-capped peaks in the distance, and a silence that was more than just the absence of sound.

I spent the night near a quiet lake under a sky that refused to go dark. The next day, thankfully, the road improved. I descended into Kautokeino, a town that felt like a border post between worlds. I visited Juhls’ Silver Gallery, part jewellery store, part art installation, and had coffee with a travelling vendor selling Sami crafts.

Borderlands and Beyond

The E45 south of Kautokeino was uneventful until a speeding truck nearly pushed me off the road. With my adrenaline pumping, I turned off at Enontekiö and took a forest road into Pallas-Yllästunturi National Park.

I camped by a cold, clear lake and spent the next day hiking and pushing my bike along MTB trails that were far too rough to ride. But the views were worth it, glacial hills, pine forests, and reindeer paths weaving into the distance.

Eventually, I crossed into Sweden near Kolari. The landscape softened again: endless birch woods, quiet lakes, and long, empty roads. I rode west toward Gällivare, where I boarded the Inlandsbanan train to Östersund and later caught the Snälltåget night train to Malmö.

Reflections

Looking back, I covered too much ground in too little time. But the sheer scale, silence, and spirit of the north made every challenge worth it.

I rode through landscapes shaped by glaciers and memory, met strangers who offered kindness in the middle of nowhere, and spent long nights alone with only the wind and the light for company.

Every day was different. Every road taught something new.

And one lesson stayed with me: if you want to know the north, really know it, you have to go further.

Go further north.

A Long Ride Through the Arctic of Europe: From the forests of Finland to the fjords of Norway and the wilderness of Swedish Lapland The

Cycling Through Norway’s Warmest Summer in Years The past few weeks in Norway have been extraordinary. From the deep fjords of the west to the

Tucked away in the rugged terrain of western Norway lies one of the country’s most challenging and least-known cycling climbs: Osafjellet. Overshadowed by more famous

Cycle Norway is dedicated to making Norway, safer and more enjoyable to experience by bike and to inspire and inform a growing audience of the opportunities available.