I would imagine most people outside of this small but weathy nation have never heard of the Tour of Norway. It doesn’t have the history of the Tour de France or the spectacle of the Giro. It’s four days of racing around a corner of southern Norway that, for most international fans, is not a big highlight on their calendar.

And yet, for Norwegian cycling and for anyone who cares about what kind of cycling future this country builds, the news that the 2026 edition is cancelled matters more than it looks on paper. A quiet line in the state budget has been erased. The consequences will be anything but quiet.

The race that stitched together a region

Since 2013, the Tour of Norway has done something simple but important: it has turned ordinary roads in the Stavanger, Bergen and other southern regions into a short, concentrated festival of cycling. It’s not just “a race in Norway”; in recent years, it’s passed through unknown towns like Egersund, Jørpeland, and Sandnes, bringing WorldTour teams such as Visma, UAE and Alpecin-Deceuninck, and putting local Norwegian riders like Alexander Kristoff on home roads in front of home crowds.

The format is modest by Grand Tour standards – four days, men and women, coastal roads, inland climbs, rain more often than not, but its role is bigger than the number of race days suggests. It has done a few things well:

- Given Norwegian teams and riders a home stage with proper international opposition.

- Turned medium-sized towns into temporary cycling capitals, with barriers, kids’ races and full cafés instead of empty high streets.

- Provided TV images of fjords, bridges and pretty wooden towns that quietly sell this part of Norway to the world.

Economically, it’s not a gold mine; the organisers openly say the race breaks even at best. The budget sits around 20 million NOK per year, according to coverage in the Norwegian press, and roughly half of that, 10 million NOK, has come from a state grant. The rest is a patchwork of team fees, local contributions and commercial partners. But sadly. that balance has now been broken.

What exactly has the government cut?

This is where the nuance matters. It’s not that “the Norwegian government no longer supports cycling”. What’s being removed is a special grant scheme for international road races – money that, in practice, has mainly gone to the Tour of Norway and the Arctic Race of Norway.

For 2024 the Tour of Norway received 10 million NOK from this pot, about half its total budget. In the proposed budget for 2026, that specific support disappears.

The Ministry of Culture and Equality’s line is blunt: keeping a dedicated scheme just for cycling events is “unfortunate” and large sports events in Norway “should be treated as equally as possible”. In their view, cycling already gets money via lottery funds, general sports support and investments in infrastructure like velodromes at Sola and Asker.

On paper, that sounds reasonable. Why should one type of event enjoy a protected funding stream when others don’t? On the ground, it looks different. Tour of Norway’s director, Roy Hegreberg, calls the cut “extremely dramatic” and says that losing millions makes arranging the race in 2026 “impossible”. The race doesn’t sell tickets, doesn’t have lottery money, and has to pay for police and security on public roads – costs that are lower or handled differently in southern Europe.

So yes, cycling as a sport is still supported. But this specific race loses its lifeline. The organisers say the remaining income simply doesn’t match the cost of running a modern, safe, UCI-level event. You don’t have to agree with them, but it’s important not to pretend the funding “sort of continues”. For Tour of Norway as we know it, the tap is effectively off.

The Arctic Race: the chosen flagship

All of this would feel different if every big Norwegian road race were treated the same way. They’re not. Up north, the Arctic Race of Norway, the “world’s northernmost stage race”, is still very much a flagship project. Over the last decade, the state has poured a total of 143 million NOK into building it up, 75 million of that under the current government. Its own impact report claims 270 million NOK worth of TV exposure, with images broadcast in 190 countries, plus 40 million NOK in extra turnover for businesses in Finnmark alone during the 2018 edition.

In other words: Arctic Race has become a regional development tool for the three northernmost counties. Municipalities invest, local businesses gear up, and volunteers treat it as a point of pride. Surveys commissioned by the race report that 96% of respondents believe it benefits local business, 97% say it improves cooperation between municipalities, and 70% think it motivates people to cycle more.

Politically, that narrative is powerful. When the Prime Minister shows up to open the 2025 Arctic Race, it’s not just about cycling; it’s about saying “the North matters” on national TV. The irony is that Arctic Race also faces cuts. Dagbladet reports it stands to lose around 5 million NOK in state support if the budget proposal holds, and its director says they are “totally dependent” on those funds to run the event. But unlike Tour of Norway, Arctic Race has already been used for years as a brand vehicle for Northern Norway, with a much longer trail of state investment behind it.

So why does one race disappear in 2026 while the other clings on?

You can come up with a few unromantic answers:

- Geography and politics: The southern region is wealthy, with oil money and robust local economies. The political case for spending national tourism money there is weaker than in the north, where depopulation and regional balance are constant issues.

- Narrative: Arctic Race has been sold successfully as a northern showcase, with professional impact studies, regional alliances and a clear “nation branding” story. Tour of Norway has done plenty for local tourism and participation, but the story hasn’t been as clear or as loud.

- Institutional backing: Arctic Race is co-organised with ASO (the company behind the Tour de France) and has built professional structures that governments like to see when they justify money.

You can argue that Tour of Norway has been doing much of the same work on a smaller scale. Linking municipalities, filling hotels, inspiring kids along the roadside, but it hasn’t become the political pet project that Arctic Race is. The result is visible now: one race fights to survive on commercial legs, the other is simply dropped.

Is the government right to cut?

Let’s be blunt. From the state’s point of view, there is a fair question here:

- Should the government permanently pay for an event that by its own admission barely breaks even and depends on a guaranteed grant every year?

- Or should such races be pushed to stand more on their own feet, with more private sponsors, more local co-funding and smarter cost control?

You can’t run everything on symbolism. Norway already spends billions every year on sports facilities, culture and health. Officials look at a 10-million-kroner line item and ask: why this, and not a swimming pool, a school roof or a local handball arena?

The Ministry’s fairness argument isn’t invented out of thin air. If you’re a triathlon organiser or a running festival director, you can reasonably ask why cycling should enjoy a unique national grant while you chase municipal crumbs and commercial partners.

On the other hand, the organisers’ frustration is also justified.

Road cycling isn’t like indoor handball. There is no stadium that was funded once and now just needs maintenance. The “arena” is public roads, and every year you start from scratch: police, barriers, safety marshals, TV production, helicopter time. You don’t have ticket income, and you can’t put a turnstile on the E39!

Other major sports events in Norway, from ski championships to rally, have enjoyed either one-off state guarantees or large subsidies to build facilities. Road cycling, by design, uses infrastructure that already exists but still has to pay heavily every year to use it safely at racing speed.

So you end up with an ugly middle ground. The race is too big and too tightly regulated to be a cheap, volunteer-driven folkefest, but too small and sponsor-poor to carry its own cost structure.

Has Tour of Norway become lazy?

That’s the harsh version of the criticism: that it leaned on the state grant instead of building a truly robust commercial base. There’s probably some truth in that. When you know 10 million NOK will arrive from Oslo every year, the pressure to reinvent the business model is softer. You can put more energy into the sporting product and the community work, and less into aggressive sponsorship hunting or new revenue streams.

But we should be careful with the “lazy” label. The race has:

- Expanded to include both men’s and women’s events, making it one of the most balanced races in Scandinavia in terms of gender equality.

- Built strong ties with local clubs and volunteers in the region.

- Brought in major teams and kept Norway visible on the UCI calendar.

The real issue may be structural rather than moral. This is a mid-sized, regional race in a high-cost country, competing for sponsorship in a cycling market where even the biggest events are struggling to keep TV numbers up.

Which brings us to the bigger picture – Road racing’s slow bleed?

The Tour of Norway is making headlines now because it’s cancelled, but it’s not the only part of the road-racing ecosystem under pressure. Even the Tour de France, the crown jewel, is feeling the strain. Recent TV data show a general decline in live audiences across core cycling countries: France, Italy, the Netherlands and Belgium have seen viewership drop by 5–7% compared to the five-year average, while Spain’s numbers have fallen by almost 30%. Outside Europe, it’s even worse; in the US, total Tour audience is now in the “tens of thousands”, down from million-plus levels during the Armstrong era.

If the global flagship is struggling to hold eyeballs, what chance does a four-day race on the Norwegian west coast have? Sponsors are not sentimental. When viewership falls and rights become fragmented across pay-TV and streaming, the return on a logo on a jersey becomes harder to justify. Mid-tier races are squeezed from both sides: rising logistics and safety costs on the one hand, softer media and sponsor income on the other. From that angle, the government cut is not the cause of the problem; it’s a symptom.

The model – TV, helicopters, WorldTour buses, rolling road closures, is expensive, and the audience is drifting. They’re not drifting away from cycling. They’re drifting somewhere else within cycling.

From helicopters to frame bags

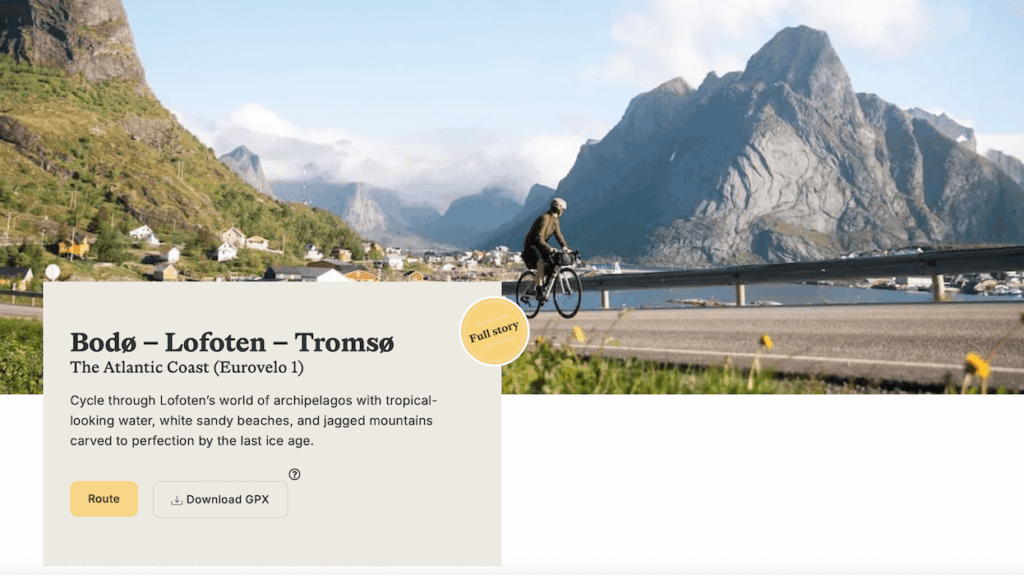

Look at where the heat is now: long-distance, self-supported ultra and bikepacking races. In Norway alone, events like Bright Midnight and Mother North have gone from niche experiments to fixtures on the international ultra calendar. Bright Midnight sends riders on roughly 1,100 km of high-country gravel, linking summer farms, fjords and mountain passes in a loop from Tolga, with around 20,000 metres of climbing. Places at these events are snapped up quickly; Bright Midnight’s 2026 edition reached capacity within weeks, and riders had to join waiting lists.

Mother North offers a similar scale of challenge: a 1,099 km loop from Lillehammer with around 16,000 metres of elevation, threading remote valleys, forests and fjords. It’s marketed not as a TV product but as “a true Norwegian bikepacking adventure”.

Then you have Nordic Chase and its Copenhagen–Oslo Gravel edition – around 800 km of mostly unpaved roads across Denmark, Sweden and Norway. Both the road and gravel editions of the Copenhagen–Oslo route are already fully booked with 100 riders each, forcing the organisers to launch an extra Berlin–Copenhagen chapter for those who missed out.

No helicopters. No police escort. No finish-line VIP tent.

Just people, bikes, bags, GPS dots – and municipal support that is often simpler and more positive than what road races face. Local councils see these events as slow-tourism magnets: riders stay in cabins, camp in official areas, buy food in shops, and post endless photos of unnamed gravel roads. They don’t close main arteries at rush hour. They don’t need hundreds of police hours. For the same or lower public cost, a region can get more riders for more days, spread across more businesses.

At the same time, global ultra events are discovering Norway in a big way. The Transcontinental Race No. 12, one of the world’s most prestigious self-supported races, will start in Trondheim in 2026, sending riders thousands of kilometres across Europe towards the Balkans and beyond. That start alone will bring a small army of riders, families, dotwatchers and content creators into the country.

If you step back, you see a pattern emerging:

- Classic road races: shorter in days, high in cost, dependent on TV and state subsidies, audience slowly eroding.

- Bikepacking / ultra races: longer in days, cheaper to host, highly photogenic for social media, entries selling out, and deeply aligned with the “experience economy” and modern adventure tourism.

Norwegian municipalities are not blind. They can count hotel nights.

What does this mean for Norway – and for Cycle Norway?

Taken together, the picture is messy but not hopeless.

On one side, Norway loses a mid-sized professional stage race in the southern region, at least for 2026. There’s talk of bringing the Tour of Norway back in 2027 if funding and partners can be found, but there are no guarantees. If it does return, it will need to lean harder on regional alliances, commercial partners and a clearer tourism narrative to justify any increased public support.

On another side, the Arctic Race of Norway is still treated as a key branding tool for the North, albeit under pressure to “stand on its own feet” in the longer term. The state has already invested heavily to build it up; politically, it’s unlikely they’ll let it collapse overnight.

And in the background, more quietly but more steadily, the bikepacking and ultra scene is exploding – with events already sold out, new routes announced, and international riders treating Norway as a bucket-list destination.

From where I sit with Cycle Norway, the lesson is fairly clear:

- Big, TV-driven events will come and go. Their survival depends on politics, broadcasters and a sponsorship economy that is getting more volatile.

- Grassroots touring, ultra and bikepacking are less glamorous on TV but far closer to what most people actually do: they ride a few days with bags, explore, get tired, get wet, get sunburned and go home with stories.

Cycle Norway has always been about that second category. Mapping routes, connecting small businesses, helping people navigate ferries, weather windows and gravel sections, it’s slow, unsexy work compared with a helicopter shot, but it’s also the part that keeps delivering year after year.

The cancellation of the Tour of Norway doesn’t change our mission; it underlines it. If the state wants value for money, there’s a strong argument that modest investments in infrastructure, signage, services and promotion for everyday riders will produce more lasting economic and social returns than a handful of high-risk, subsidy-dependent road races.

That doesn’t mean the Tour of Norway doesn’t matter. It does. It gave kids in Rogaland heroes they could see on their doorstep. It showed that you can line a Norwegian road with barriers and bunting and create a folk festival. Losing it is a blow, especially for western Norway. But the story of cycling in this country is not decided by one line in a state budget.

If anything, the shift we’re seeing away from relying on a helicopter and a TV truck, towards frame bags and GPX files, might actually fit Norway better. A long, thin country with ferries, mountain passes, unstable weather and endless quiet roads was always more suited to riding through than watching from the road.

So yes, we should be angry that millions of NOK disappear from a race that has done good things for participation and tourism. And yes, we should challenge the government’s simplistic “fairness” logic when road cycling faces unique costs.

But we should also be honest: the future here will be built by riders who pin on a number in Tolga, Lillehammer, Copenhagen or Trondheim, load their bikes, and go and actually ride Norway, not just watch it.

For Cycle Norway, that’s where we’ll keep putting our energy. Connecting those dots. Giving context and information. Making it easier for a rider heading to Bright Midnight, Mother North, Nordic Chase or the Transcontinental start line in Trondheim to stay longer, explore more, and spend their money in small Norwegian communities.

The Tour of Norway may be gone in 2026. The question now is whether Norway is willing to back the kind of cycling that’s clearly on the rise or whether we’ll still be arguing over helicopter airtime while the real action quietly rolls past on gravel.