Pedalling to the Edge: Norway’s Hidden World Heritage Archipelago

There’s a point, somewhere off the Helgeland coast, where the mainland disappears behind you and the islands begin. Not the tourist-trodden kind with waffle huts

There’s a point, somewhere off the Helgeland coast, where the mainland disappears behind you and the islands begin. Not the tourist-trodden kind with waffle huts and Instagram signs — but the sort of islands that seem to drift slightly outside time, where sea, stone, bird, and human have lived in uneasy harmony for longer than memory holds. Vega is one of those places.

For the cyclist, Vega isn’t the sort of place you stumble upon. You plan for it. You wait for the weather. You make the ferry times. You pack light and hope the wind is with you. And then, once you’re there, the whole island opens up like a forgotten page in a book no one’s read in a while — worn but still eloquent.

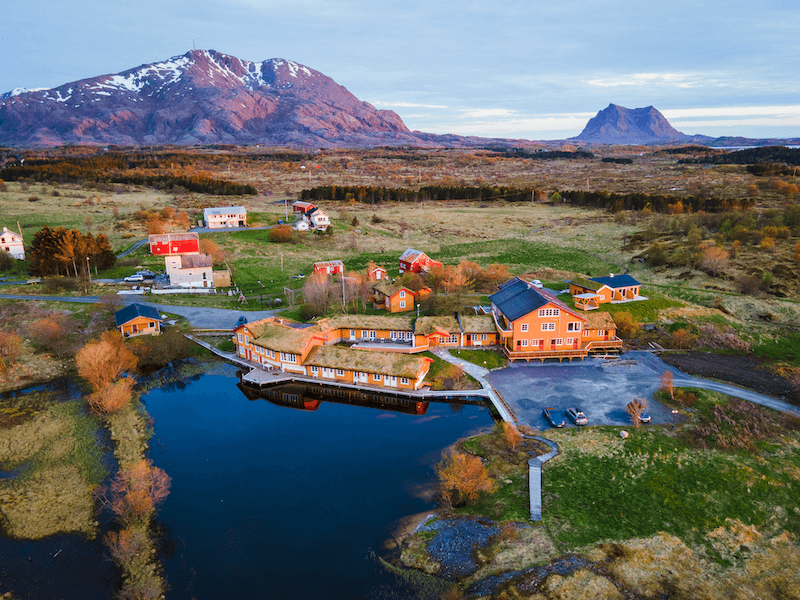

Geographically speaking, Vega is a world away from the mainland. The island sits in the middle of a 6,500-island archipelago off the coast of Nordland, part of what’s known as the Helgeland coast — Norway’s most fragmented, ocean-battered shoreline. Unlike the towering peaks of Lofoten or the deep glacial fjords of the west, Vega’s geology is quiet. Low-lying hills roll gently toward the sea. Granite outcrops rise like broken knuckles from the earth. The beaches, surprisingly, are soft and sandy — windswept and quiet, if not exactly sunbathing territory.

But Vega’s most remarkable feature isn’t its shape — it’s what humans have done with it. Or, more accurately, what they haven’t done.

In 2004, the Vega Archipelago was inscribed on UNESCO’s World Heritage List. But unlike most sites that make the list for their buildings or ruins, Vega was chosen for something less obvious: the way generations of fishermen and women have lived with the eider duck.

Yes, ducks. For over 1,500 years, the people of Vega built small houses for wild eider ducks, harvested their down (after the birds left), and cared for them during nesting season. It’s a relationship of mutual benefit, one that required knowledge, patience, and restraint — things that modern progress often tramples in its rush forward.

This way of life — eider farming, as it’s sometimes called, is barely practised today. But the tradition is still visible in places like the E-Hus Museum, where the old shelters and stories are preserved. UNESCO called it “an outstanding example of sustainable living” in a harsh environment. And when you cycle around the island, you start to understand why.

Vega isn’t a large island — you can cycle from end to end in under an hour if you’re not stopping. But of course, you will. The main road loops around in a sort of ragged horseshoe, with gravel tracks and smaller paths spidering off into fields, coves, and coastal trails. Traffic is almost non-existent — a car here, a tractor there. The roads are of good quality for the most part, with the odd potholed stretch reminding you this is still rural Norway.

Photo credit: Ken Bayne

What makes cycling Vega different from the mainland is the rhythm. The island moves slower. Wind and weather dictate your pace more than gradients or deadlines. You stop to watch birds — sea eagles, oystercatchers, herons. You pull over when a herd of sheep blocks the road. You end up in conversations at ferry landings that last too long and go nowhere, but feel right.

There’s a sense, almost a whisper, that you’re somewhere that was never meant for mass tourism. And that’s a gift.

Around 1,000 people live on Vega today — most of them spread across small hamlets and farms. The main settlement is Gladstad, where you’ll find a Coop, a petrol station, a school, and a quiet dignity that seems increasingly rare in a world addicted to spectacle.

Many of Vega’s inhabitants are older. Young people, like in so many remote parts of Norway, often leave for the cities. But some return. And others — tired of urban speed — come here to reset, to raise families, or just to listen.

The island isn’t frozen in time, but neither is it rushing toward the future. Fishing still matters. Farming too, though on a smaller scale. Some run tourism-related businesses, but these are usually modest: kayak rentals, cafés with erratic hours, or guesthouses run from converted barns.

There’s a stillness to the social life here, not in a cold or unfriendly way, but in a manner that requires patience. You arrive, and the island watches to see what you’ll do with yourself.

There are beaches on Vega, and they’re better than you’d think. Eidemstranda is the best known, a long curve of white sand facing west, backed by grass and birch trees. On a warm day in late July, you might even brave the water. But Vega’s real magic is not in the swimming, it’s in the sitting. The watching. The long shadows in the evening and the wind sifting through sedge grass.

There are hiking trails too, most notably the climb up Vegatrappa – a 1,000-step staircase built up the mountain Ravnfloget. The view at the top, especially at sunset, is unforgettable. The sea stretches in every direction, the mainland a faded line to the east, and the silence so complete you can hear your own heartbeat.

You can also kayak between islets, walk old post roads, or just explore the coastline on foot, where driftwood piles like shipwreck bones and old boat houses lean into the wind.

Accommodation on Vega is straightforward. Don’t expect boutique hotels or infinity pools. Instead, you’ll find a handful of guesthouses, fisherman’s cabins (rorbuer), private rentals, and campsites. Nes Brygge is popular, with its dockside location and practical rooms. There’s also Vega Havhotell, a bit more upscale, known for its food and storytelling. Wild camping is possible, though as always, show respect and ask if near farmland.

Most places fill up quickly in high summer, so booking ahead, even just by phone, is wise. But outside of July, you’ll often find a place just by asking.

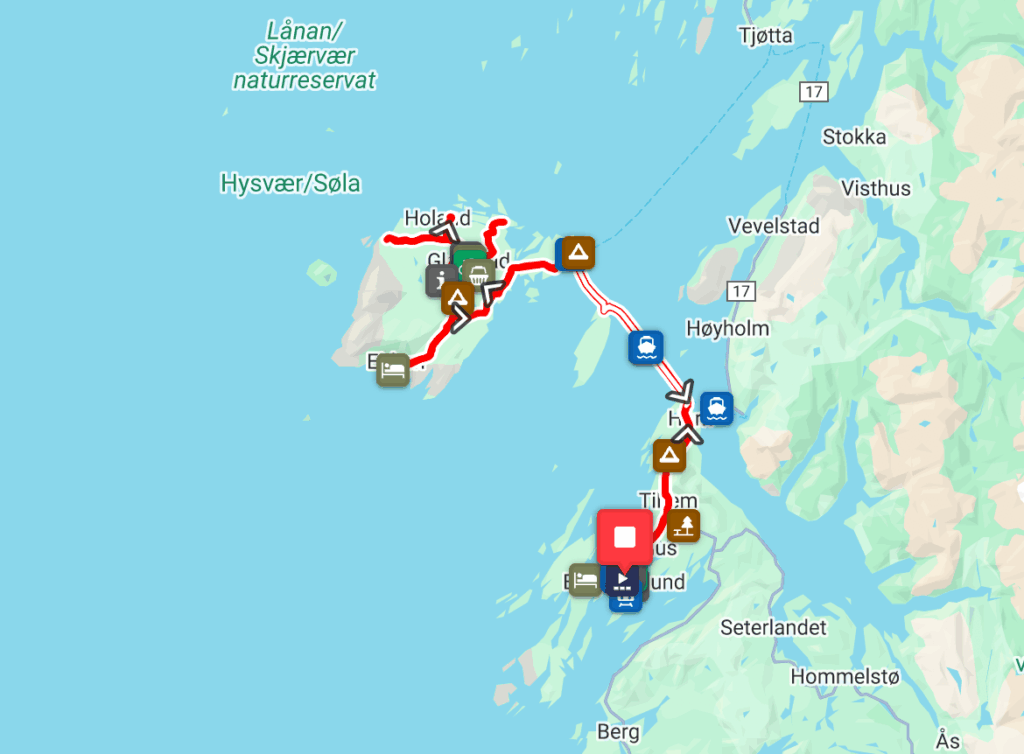

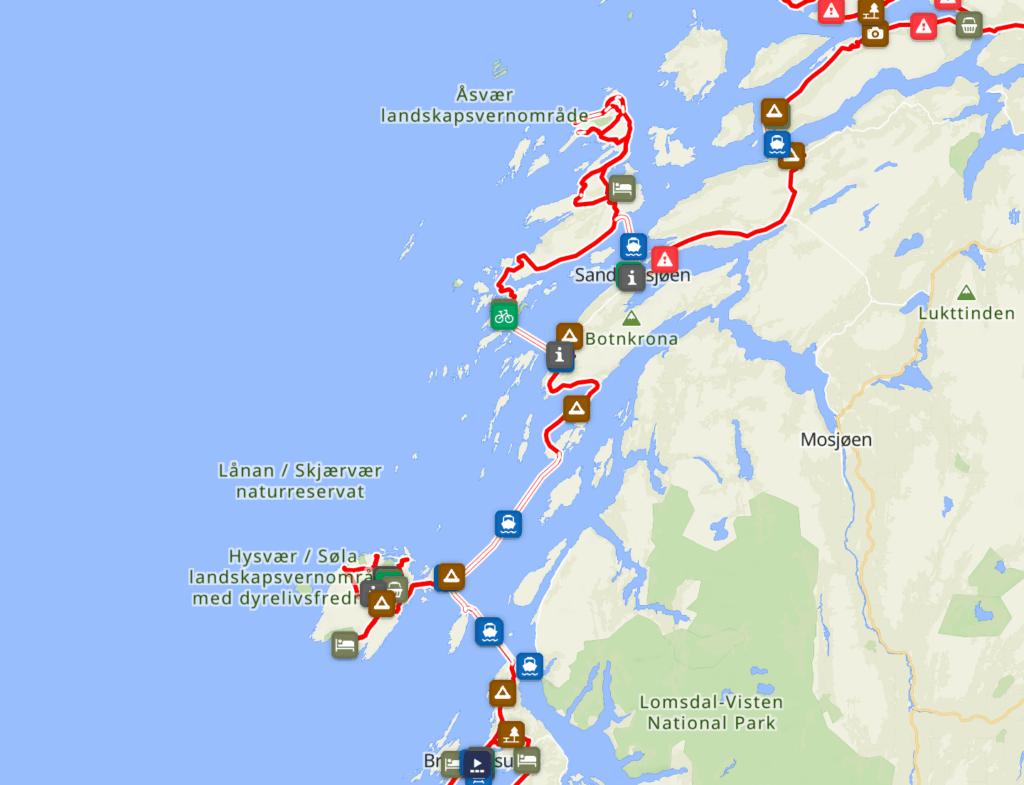

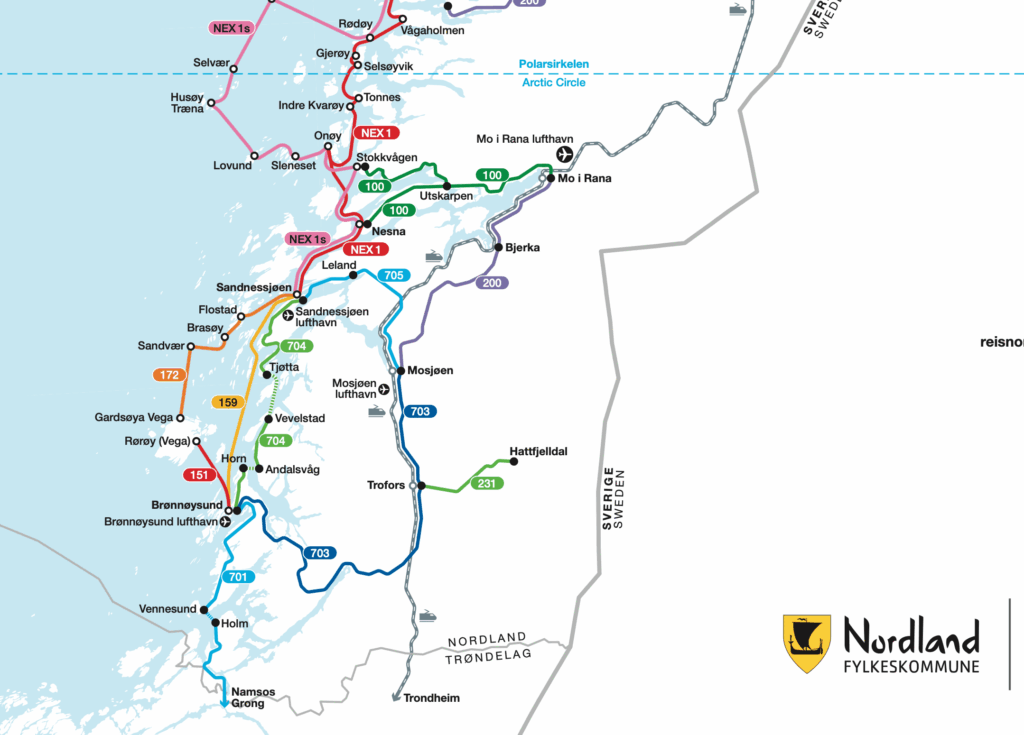

Reaching Vega without flying is part of the adventure. The usual route starts from the mainland town of Brønnøysund, which you can reach by bike by taking the famous Trondheim to Bodø route known as Kystriksveien by locals. From Brønnøysund, you take a local ferry run by Torghatten Trafikkselskap. The main ferry to Vega lands at Rørøy, and the schedule varies seasonally, sometimes just a few times a day. Bicycles are allowed and there’s no need to pre-book, though summer weekends can get crowded.

Ferries

From the ferry port, it’s about 6 km to Gladstad – the island’s modest centre.

There are also connections to other islands in the archipelago, like Ylvingen, for those wanting to island-hop slowly through this quiet world. Check out our recommended island-hopping route (below) up this incredible coast.

Ferries for the whole area can be found ici

Réflexions finales

Vega is not for everyone. It’s not flashy. It doesn’t shout. But for those who listen, cyclists especially, it offers something rare: a sense of human history that hasn’t been paved over, and a landscape where silence still has meaning. Whether you stay for a day or a week, the island leaves its mark not in what you do, but in how you feel after leaving.

Vega asks nothing of you, but if you bring curiosity, respect, and a willingness to slow down, it quietly offers everything for the simple pleasure of a bike ride.

There’s a point, somewhere off the Helgeland coast, where the mainland disappears behind you and the islands begin. Not the tourist-trodden kind with waffle huts

Monter sur la route la plus haute d'Oslo : La bête cachée de Gyrihaugen Si vous faites du vélo dans la région d'Oslo et que vous pensez que le terrain n'est constitué que de chemins forestiers ondulants

World Class Bike Photography in Norway - Part 2 : Ce blog est la suite de [Part 1] Nous avons pris la route avec un plan approximatif, un vélo déglingué et une voiture...

Cycle Norway a pour mission de rendre la Norvège plus sûre et plus agréable à parcourir à vélo et d'inspirer et d'informer un public de plus en plus large sur les possibilités qui s'offrent à lui.